Why It's Difficult (Or Impossible) To Avoid Training Injuries

And how to minimize them

Injuries occur when you place stress on tissue that it cannot handle. Those injuries can be acute, chronic, or somewhere in between. For example, you may put more stress on your lower back than it can handle for a single rep of squats, which results in an acute lower back injury. But you may also experience plantar fasciitis due to the cumulative stress of months of marathon training. It’s also not one or the other, as injuries can result from both acute and chronic causative factors. Cumulative stress can load the gun, while an acute incident can pull the trigger.

But stress is only one side of the equation. It alone won’t tell you whether an injury will occur. We also need to consider capacity1, which is our tissue’s ability to handle that stress. Capacity is best improved through a systematic and incremental increase in stress so that we a) stay within our current capacity while b) driving adaptation to increase that capacity. In other words, we need to do enough to increase tissue resilience without exceeding current limits to cause injury or set back the process.

What makes this relationship difficult to manage?

Capacity is specific to a movement, technique, load, AND volume. Adaptation is specific, to a point. Doing back squats for three sets of five at 135 pounds doesn’t then allow us to do front squats for 4 sets of 8 at 140 pounds. We are certainly better off than we would have been had we not done the back squats, but capacity carryover is somewhat specific to each one of these variables. For every variable you change, the relationship between stress and capacity gets looser. This is why programs that involve a high degree of variety can pose a long-term safety risk, especially if the person writing the program is playing fast and loose with heavy loads and high volume.

Your capacity is not static. Capacity is affected by many variables, including but not limited to:

Health status (sick or feeling physically unwell)

Sleep

Psychological stress or mood

Focus

Nutrition

Mental or physical fatigue

Workout consistency

Technique consistency

A lifter who wants to get stronger needs enough stress to elicit adaptation without exceeding their capacity, which, as I’ve just explained, can be unpredictable. But a couple of key concepts will help you understand the relationship between stress and capacity.

Increases in capacity are not perfectly linear or predictable

As a lifting beginner, it’s not uncommon to be able to add weight to the bar every workout for a given exercise. Some of these gains are due to structural adaptations in the muscles, but most are due to improved neuromuscular coordination. Basically, communication between your nervous system and your muscles improves, leading to better coordination and strength.

So in the beginning, the relationship may seem “tighter” between stress and adaptation. You lift a given weight, adapt, and can lift more the next time. But there are two caveats here:

You may be able to increase because you’re drastically undershooting your true strength potential. In other words, your “improvements” are really just you closing the gap between what you’re lifting and what you should be lifting.

Neurological gains are much faster than structural (muscular) gains

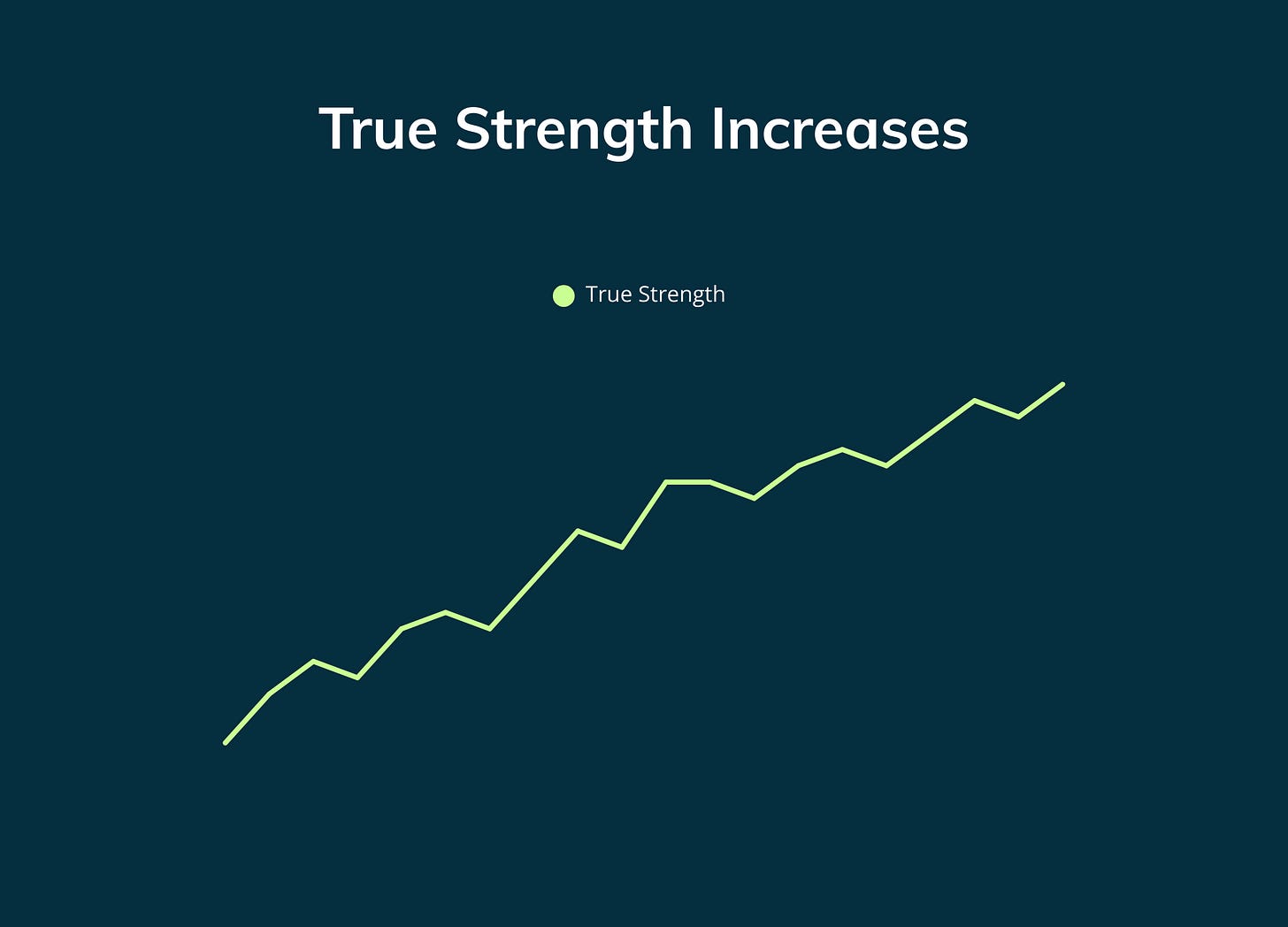

But as you get more advanced—and often even as a beginner—you won’t always see progress as a straight diagonal line. That’s because progress isn’t truly linear. Adaptation to stress can be kinda messy and unpredictable. It’s best to take a somewhat zoomed-out look at progress to determine whether you’re actually getting stronger.

For instance, if you can squat 135 pounds for three sets of 5 in a given week, although you might expect to be able to lift 140 pounds for three sets of 5 the following week, you may not be able to. Hell, you’re not always guaranteed to be able to lift the same weight from workout to workout. But as long as you’re generally improving, the day-to-day performance matters less.

Capacity fluctuates throughout the week

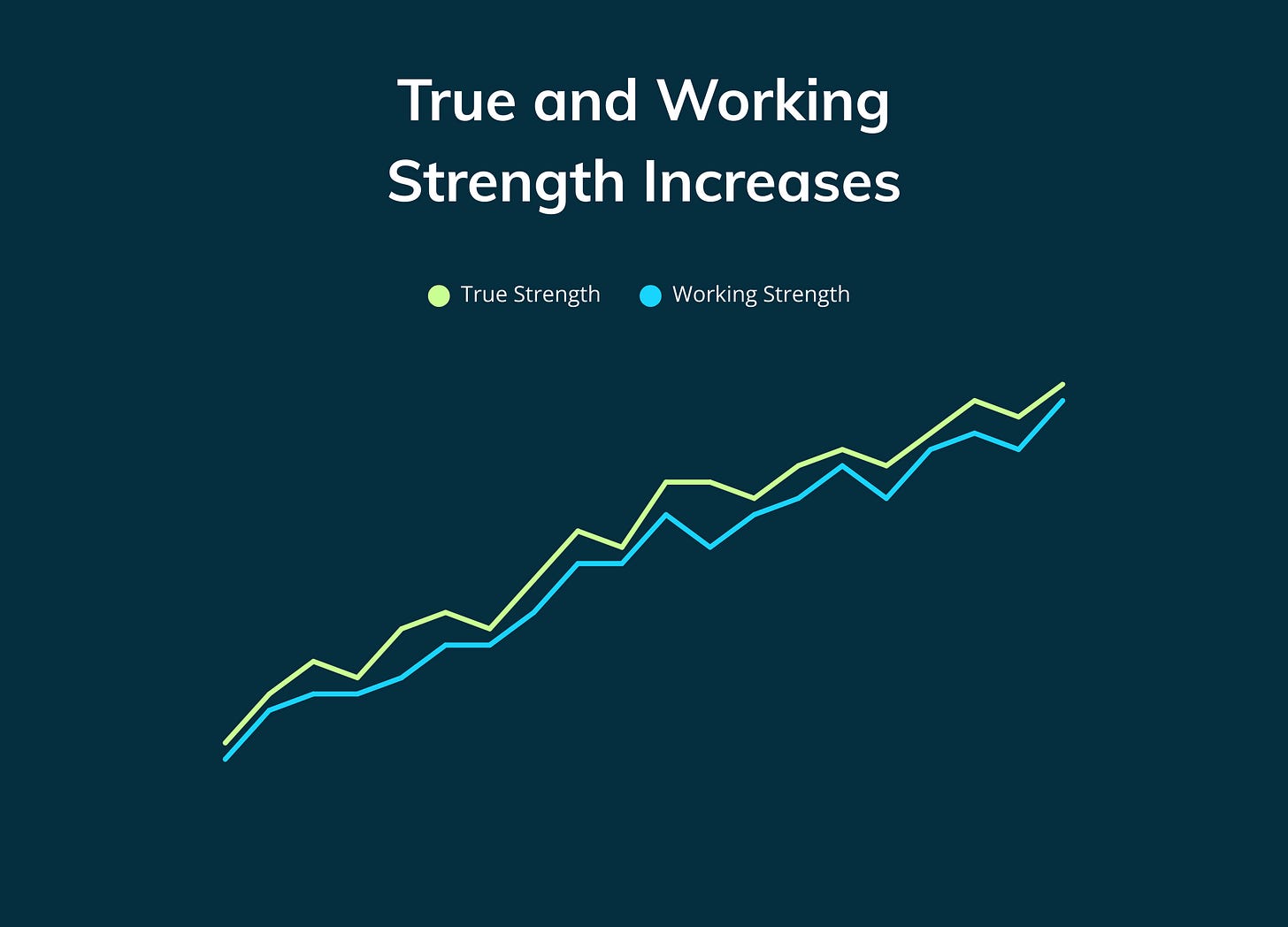

Imagine, as I mentioned before, a broader “true” change in your capacity or strength for an exercise. It is a real number, but you often won’t be able to determine it with complete accuracy. Imagine that number as a jaggedly increasing line like this.

Now, imagine another line underneath that represents what capacity we actually have access to on any given day. We can call this “working capacity” or “working strength”.

It’s difficult enough to determine your capacity on any given day using the first line, so imagine how difficult it is when you add the second. You can now see why hardcoded prescriptions to increase weight on a set schedule may be problematic to implement.

If your “true” capacity starts at 100%, your working capacity may range from 80% to 95%2 of that, depending on the factors at play and their extent. There is no guarantee that the you that shows up on the workout that calls for more weight will be up to the task. If your workout calls for a performance that requires 90% of your capacity for a given exercise, but your working capacity is only 85%, what do you think is going to happen?

Capacity is specific to the activity

Strength (or capacity) is specific to the task's demands. Our bodies are very efficient in that way. Adaptation is physiologically and metabolically expensive, so it doesn’t make sense to improve anything other than what must be improved. To be clear, strength is generally transferable, so some of it absolutely carries over to different tasks. But you cannot expect all of it to.

Which means that the greater variation in how you perform a movement, the more the stress of said movement divorces your capacity for it. In other words, if you want to ensure you have the capacity for something, it needs to look similar enough to equip you to handle it. So while minor technique-related aberrations aren’t typically a problem, large ones absolutely can be. And these get amplified by your working capacity. If your daily working capacity is high, you can handle more deviation. If your daily working capacity is lower relative to your true capacity, you can handle less deviation.

So, how do we manage stress better?

I’ve told you important truths to help you understand how to determine capacity. What are some practical ways we can stay in our “adaptation yet within capacity” window?

Slow down progression

The easiest way to mitigate risk is to slow down your progression. A longer, more gradual progression reduces the risk of exceeding your capacity. Your muscles and connective tissue have more time to adapt, and the only real downside is that progress takes a little longer. Here are a few ways you can slow down progression:

Incorporate double progression. Rather than increasing weight every session, use a rep range. You stay at the same weight until you reach the top of the range, and once you move up to the next weight, you can drop lower in the range.

Increase weight at more infrequent intervals. I used to believe staying at the same weight for longer than a week or two meant missing out on my crucial gain window. But even at the same weight, you’re still adapting. There are just diminishing returns. Wait a week or two to move up, after your RPE has dropped for a given weight and rep count.

Use a variable to measure effort, such as Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) or Reps In Reserve (RIR)3. If your only way to determine that you’re getting stronger is to add weight or reps, it may encourage premature or unnecessary increases in load or volume. RPE (or RIR) gives you a way to measure progress without actually changing the external stress. Lifting the same weight and reps at a lower RPE indicates you have gotten stronger without risking forced additional stress.

Stay away from complete muscular failure

Failure sets can help determine your limits, but they can also be more precarious in two ways. True muscular failure generates disproportionately more fatigue than stopping just short of failure, and, in my experience, technique breakdown is far more likely when approaching failure.

Using the RPE system above, keep your sets in the 6-9 range, meaning leaving 1-4 reps in the tank, depending on the exercise. Your reps will be stimulating without an excessive risk of form breakdown.

Learn when to call audibles

Some days, you will feel like things are “off”. A particular muscle or joint may feel tweaky or weak. That doesn’t always mean you can’t perform as expected, but it may be a sign that you need to be extra careful. I’m the last person to recommend throwing in the towel at the slightest provocation—I think that creates a dangerous slippery slope for chronic underperformance—but you will learn throughout your lifting career what you can train through and what’s a showstopper.

You could try using your last warm-up set as a litmus test for the performance to follow. The last set is usually heavy enough to gauge your strength, yet early enough to make useful preemptive adjustments.

The skill of creating ad hoc training modifications is a superpower for injury mitigation, but to become an expert, you must first take your licks. It’s probably the most valuable item in this list, but it’s a painful learning process.

So you got injured, now what?

A full breakdown of what to do when you experience pain or injury is outside the scope of this already very long article, but here’s what you need to understand about both of these things.

Injuries are temporary. A large majority of weight-training injuries heal on their own over time. Do not catastrophize; do not tell yourself this is the end of your training career. I’ve injured myself countless times in the gym. Those injuries range from small muscle and joint tweaks to debilitating muscle strains and tendinitis that have drastically decreased my quality of life. But none of them have been permanent.

Do what you can to maintain training momentum. I wrote an article detailing several strategies for modifying training for pain or injury. Continuing to train to the best of your ability is not being obstinate. Our bodies heal best through movement and stimulation, not idleness. Repeatedly overcoming injuries will also boost your self-efficacy.

Every injury is a learning opportunity. Although injuries are normal and unavoidable, that doesn’t mean we need to keep slowing down progress by making the same mistakes over and over again. Blaming technique is still fashionable, but it does not, in isolation, cause injuries. In my experience, it only presents a problem when it’s sloppy, and your reps look wildly different. I would look at load management before blaming your technique. You did something the tissue couldn’t handle by doing too much too soon.

How you respond to injuries is far more important than the injuries themselves. Can you stay the course when things don’t go as planned and you don’t feel 100%? Find a way imperfectly forward.

Summary

Put simply, injuries result from stress that outstrips capacity. Capacity, unfortunately, has a myriad of inputs that make it difficult to determine precisely on any given day. But if you’re able to tap into strategies that make increases in stress more manageable, you can give yourself a fighting chance.

The harsh reality is that you cannot completely avoid injury if you’re training with great effort. There are too many variables at play, and stress and capacity are too granular and unpredictable to stay on top of with any degree of certainty.

But the broader and infinitely more important message is that injuries and pain are part of physically pushing yourself. There will never exist a utopia where you can perfectly manage stress. Luckily, our bodies are great at repairing themselves.

Now, to close out this already too-long article. Injuries are part of the game. Do what you can to minimize them, but when they do happen, learn from them and move on. Godspeed.

For the context of this article, we will consider strength and capacity to be interchangeable. You could also use the term “resilience” to refer to strength in a defensive capacity rather than an offensive one.

I made these percentages up, but they should illustrate the point.

RPE stands for rating of perceived exertion. It’s a 1-10 scale most commonly used as the inverse of RIR (reps in reserve). An RPE of 9, for example, would be equivalent to an RIR of 1, meaning you could have only done one more repetition of an exercise. True failure is represented by RPE 10 or RIR 0.